General Information About Vaginal Cancer

Carcinomas of the vagina are uncommon tumors comprising about 2% of the cancers that arise in the female genital system.[1] Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) accounts for approximately 80% to 90% of vaginal cancer cases and adenocarcinoma accounts for 5% to 10% of vaginal cancer cases.[1]

Rarely, melanomas (often nonpigmented), sarcomas, small-cell carcinomas, lymphomas, or carcinoid tumors have been described as primary vaginal cancers. The natural history, prognosis, and treatment of other primary vaginal cancers are different and are not covered in this summary.

Distant hematogenous metastases occur most commonly in the lungs, and, less frequently, in the liver, bone, or other sites.[1]

The American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system classifies tumors in the vagina that involve the cervix of women with an intact uterus as cervical cancers.[2] Therefore, tumors that originated in the apical vagina but extend to the cervix are classified as cervical cancers. For more information, see Cervical Cancer Treatment.

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from vaginal and other female genital cancer in the United States in 2024:[3]

- New cases: 8,650.

- Deaths: 1,870.

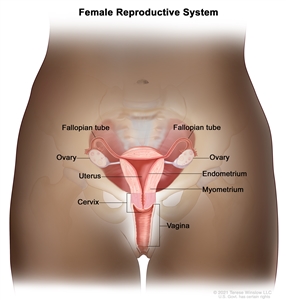

Anatomy

Normal female reproductive system anatomy.

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. Other risk factors for vaginal cancer include the following:

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. SCC of the vagina is associated with a high rate of infection with oncogenic strains of HPV. SCC of the vagina and SCC of the cervix have many common risk factors.[4,5,6] HPV infection has also been described in a case of vaginal adenocarcinoma.[6] For more information, see Cervical Cancer Treatment.

- Diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in utero. A rare form of adenocarcinoma, known as clear cell carcinoma, occurs in association with in utero exposure to DES, with a peak incidence before age 30 years. This association was first reported in 1971.[7] The incidence of this disease, which is highest for those exposed during the first trimester, peaked in the mid-1970s, reflecting the use of DES in the 1950s. It is extremely rare now.[1] However, women with a known history of in utero DES exposure should be carefully monitored for possible presence of this tumor. (This association was mainly applicable to vaginal cancers diagnosed in younger women since adenocarcinomas that are not associated with DES exposure occur primarily during postmenopausal years.)

Vaginal adenosis is most commonly found in young women who had in utero exposure to DES and may coexist with a clear cell adenocarcinoma, although it rarely progresses to adenocarcinoma. Adenosis is replaced by squamous metaplasia, which occurs naturally, and requires follow-up but not removal.

- History of hysterectomy. Women who have had a hysterectomy for benign, premalignant, or malignant disease are at risk of vaginal carcinomas.[8] In a retrospective series of 100 women studied over 30 years, 50% had undergone hysterectomy before the diagnosis of vaginal cancer.[8] In the posthysterectomy group, 31 of 50 women (62%) developed cancers limited to the upper third of the vagina. In women who had not previously undergone hysterectomy, upper vaginal lesions were found in 17 of 50 women (34%).

Clinical Features

Although early vaginal cancer may not cause noticeable signs or symptoms, possible signs and symptoms of vaginal cancer include the following:

- Metrorrhagia.

- Dyspareunia.

- Pelvic pain.

- Vaginal mass.

- Dysuria.

- Constipation.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The following procedures may be used to diagnose vaginal cancer:

- History and physical examination.

- Pelvic examination.

- Cervical cytology (Pap smear).

- HPV testing.

- Colposcopy.

- Biopsy. If the cervix is intact, biopsies are mandatory to rule out a primary carcinoma of the cervix. Carcinoma of the vulva should also be ruled out.

Prognostic Factors

Prognosis depends primarily on the stage of disease, but survival is reduced among women with the following features:

- Age older than 60 years.

- Symptomatic at the time of diagnosis.

- Lesions of the middle and lower third of the vagina.

- Poorly differentiated tumors.

In addition, the length of vaginal wall involvement has been found to be associated with survival and stage of disease in patients with vaginal SCC.

Follow-Up After Treatment

Similar to other gynecologic malignancies, the evidence base for surveillance after initial management of vaginal cancer is weak because of a lack of randomized or prospective clinical studies.[9] There is no reliable evidence that routine cytological or imaging procedures in patients improves health outcomes beyond what is achieved by careful physical examination and assessment of new symptoms. Therefore, outside the investigational setting, imaging procedures may be reserved for patients in whom physical examination or symptoms raise clinical suspicion of a recurrence or progression.

References:

-

Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

-

Vagina. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 641–7.

-

American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2024. American Cancer Society, 2024. Available online. Last accessed June 21, 2024.

-

Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Schwartz SM, et al.: A population-based study of squamous cell vaginal cancer: HPV and cofactors. Gynecol Oncol 84 (2): 263-70, 2002.

-

Parkin DM: The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 118 (12): 3030-44, 2006.

-

Ikenberg H, Runge M, Göppinger A, et al.: Human papillomavirus DNA in invasive carcinoma of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol 76 (3 Pt 1): 432-8, 1990.

-

Herbst AL, Ulfelder H, Poskanzer DC: Adenocarcinoma of the vagina. Association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. N Engl J Med 284 (15): 878-81, 1971.

-

Stock RG, Chen AS, Seski J: A 30-year experience in the management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: analysis of prognostic factors and treatment modalities. Gynecol Oncol 56 (1): 45-52, 1995.

-

Salani R, Backes FJ, Fung MF, et al.: Posttreatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommendations. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204 (6): 466-78, 2011.

Stage Information for Vaginal Cancer

FIGO Staging System

The Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) have designated staging to define vaginal cancer. The FIGO system is the most commonly used staging system for vaginal cancer.[1,2,3]

Table 1. Carcinoma of the Vaginaa

| FIGO Nomenclature |

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. |

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology.[1,2] |

| Stage I |

The carcinoma is limited to the vaginal wall. |

| Stage II |

The carcinoma has involved the subvaginal tissue but has not extended to the pelvic wall. |

| Stage III |

The carcinoma has extended to the pelvic wall. |

| Stage IV |

The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has involved the mucosa of the bladder or rectum; bullous edemas as such does not permit a case to be allotted to stage IV. |

| IVa - Tumor invades bladder and/or rectal mucosa and/or direct extension beyond the true pelvis. |

| IVb - Spread to distant organs. |

In addition, the FIGO staging system incorporates a modified World Health Organization prognostic scoring system. The scores from the eight risk factors are summed and incorporated into the FIGO stage, separated by a colon (e.g., stage II:4, stage IV:9, etc.). Unfortunately, a variety of risk-scoring systems have been published, making comparisons of results difficult.

References:

-

FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology: Current FIGO staging for cancer of the vagina, fallopian tube, ovary, and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 105 (1): 3-4, 2009.

-

Adams TS, Rogers LJ, Cuello MA: Cancer of the vagina: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 155 (Suppl 1): 19-27, 2021.

-

Vagina. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 641–7.

Treatment Option Overview for Vaginal Cancer

Given the rarity of vaginal cancer, studies are limited to retrospective case series, usually from single-referral institutions.[Level of evidence C2] During the long span of time covered by these case series, available staging tests and radiation techniques often changed, including the shift to high-energy accelerators and conformal and intensity-modulated radiation therapy.[1,2] Comparing treatment approaches is further complicated by the frequent failure of investigators to provide precise staging criteria (particularly for stage I vs. stage II disease) or criteria for the choice of treatment modality. This has led to a broad range of reported disease control and survival rates for any given stage and treatment modality.[3]

Factors to be considered in planning therapy for vaginal cancer include the following:

- Stage and size of the lesion.

- Ability to retain a functional vagina.

- Presence or absence of the uterus.

- Whether the patient has received previous pelvic radiation therapy.

- Whether the lymphatics drain to pelvic or inguinal nodes or both, depending on tumor location.

- Proximity of the vagina to the bladder or rectum. This limits surgical treatment options and increases short-term and long-term surgical complications and functional deficits.

- Proximity to radiosensitive organs or organs that preclude radical resection without unacceptable functional deficits (e.g., bladder, rectum, urethra).

Radiation-induced damage to nearby organs may include:[1,2]

- Rectovaginal fistulas.

- Vesicovaginal fistulas.

- Rectal or vaginal strictures.

- Cystitis.

- Proctitis.

- Premature menopause from ovarian damage.

- Soft tissue or bone necrosis.

Management of the extremely rare vaginal clear cell carcinoma is similar to the management of squamous cell carcinoma. However, techniques that preserve vaginal and ovarian function should be strongly considered during treatment planning, given the young age of the patients at diagnosis.[4]

Table 2. Treatment Options for Vaginal Cancer

| Stage ( FIGOStaging System) |

Treatment Options |

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; VaIN = vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. |

| VaIN (this stage is not recognized by FIGO) |

Laser therapy |

| Wide local excision |

| Vaginectomy |

| Intravaginal chemotherapy |

| Intracavitary radiation therapy |

| Imiquimod |

| Stage I vaginal cancer |

SCC |

Radiation therapy |

| Surgery |

| Adenocarcinoma |

Surgery |

| Radiation therapy |

| Combined local therapy |

| Stages II, III, and IVa vaginal cancer (SCC and adenocarcinoma) |

Radiation therapy |

| Surgery |

| Chemoradiation |

| Stage IVb vaginal cancer (SCC and adenocarcinoma) |

Radiation therapy |

For patients with carcinoma of the vagina in its early stages, radiation therapy or surgery or a combination of these treatments are standard. Data from randomized trials are lacking, and the choice of therapy is generally determined by institutional experience and the factors listed above.[3]

For patients with stages III and IVa disease, radiation therapy is standard and includes external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT), alone or with brachytherapy. Regional lymph nodes are included in the radiation portal. When used alone, EBRT involves a tumor dose of 65 Gy to 70 Gy, using shrinking fields, delivered within 6 to 7 weeks. Intracavitary brachytherapy provides insufficient dose penetration for locally advanced tumors, so interstitial brachytherapy is used if brachytherapy is given.[3,5]

For patients with stage IVb or recurrent disease that cannot be managed with local treatments, current therapy is inadequate. No established anticancer drugs have demonstrated proven clinical benefit, although patients are often treated with regimens used to treat cervical cancer. Concurrent chemotherapy, using fluorouracil or cisplatin-based therapy, and radiation are sometimes advocated, based solely on extrapolation from cervical cancer management strategies.[6,7,8] Evidence is limited to small case series and the incremental impact on survival and local control is not well defined.[Level of evidence C3]

Local control is a problem with bulky tumors. Some investigators have also used concurrent chemotherapy with agents such as cisplatin, bleomycin, mitomycin, floxuridine, and vincristine without improved outcomes.[1] It is an extrapolation from treatment approaches used in cervical cancer, based on shared etiologic and risk factors.

Because vaginal cancer is rare, these patients are candidates for clinical trials of anticancer drugs and/or radiosensitizers to attempt to improve survival or local control. Discussion of clinical trials should be considered with eligible patients. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Fluorouracil Dosing

The DPYD gene encodes an enzyme that catabolizes pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines, like capecitabine and fluorouracil. An estimated 1% to 2% of the population has germline pathogenic variants in DPYD, which lead to reduced DPD protein function and an accumulation of pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines in the body.[9,10] Patients with the DPYD*2A variant who receive fluoropyrimidines may experience severe, life-threatening toxicities that are sometimes fatal. Many other DPYD variants have been identified, with a range of clinical effects.[9,10,11] Fluoropyrimidine avoidance or a dose reduction of 50% may be recommended based on the patient's DPYD genotype and number of functioning DPYD alleles.[12,13,14]DPYD genetic testing costs less than $200, but insurance coverage varies due to a lack of national guidelines.[15] In addition, testing may delay therapy by 2 weeks, which would not be advisable in urgent situations. This controversial issue requires further evaluation.[16]

References:

-

Frank SJ, Jhingran A, Levenback C, et al.: Definitive radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 62 (1): 138-47, 2005.

-

Tran PT, Su Z, Lee P, et al.: Prognostic factors for outcomes and complications for primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina treated with radiation. Gynecol Oncol 105 (3): 641-9, 2007.

-

Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

-

Senekjian EK, Frey KW, Anderson D, et al.: Local therapy in stage I clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina. Cancer 60 (6): 1319-24, 1987.

-

Chyle V, Zagars GK, Wheeler JA, et al.: Definitive radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vagina: outcome and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 35 (5): 891-905, 1996.

-

Grigsby PW: Vaginal cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 3 (2): 125-30, 2002.

-

Dalrymple JL, Russell AH, Lee SW, et al.: Chemoradiation for primary invasive squamous carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Gynecol Cancer 14 (1): 110-7, 2004 Jan-Feb.

-

Samant R, Lau B, E C, et al.: Primary vaginal cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiation using Cis-platinum. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 69 (3): 746-50, 2007.

-

Sharma BB, Rai K, Blunt H, et al.: Pathogenic DPYD Variants and Treatment-Related Mortality in Patients Receiving Fluoropyrimidine Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 26 (12): 1008-1016, 2021.

-

Lam SW, Guchelaar HJ, Boven E: The role of pharmacogenetics in capecitabine efficacy and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 50: 9-22, 2016.

-

Shakeel F, Fang F, Kwon JW, et al.: Patients carrying DPYD variant alleles have increased risk of severe toxicity and related treatment modifications during fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics 22 (3): 145-155, 2021.

-

Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM, et al.: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103 (2): 210-216, 2018.

-

Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al.: DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: a prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol 19 (11): 1459-1467, 2018.

-

Lau-Min KS, Varughese LA, Nelson MN, et al.: Preemptive pharmacogenetic testing to guide chemotherapy dosing in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: a qualitative study of barriers to implementation. BMC Cancer 22 (1): 47, 2022.

-

Brooks GA, Tapp S, Daly AT, et al.: Cost-effectiveness of DPYD Genotyping Prior to Fluoropyrimidine-based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 21 (3): e189-e195, 2022.

-

Baker SD, Bates SE, Brooks GA, et al.: DPYD Testing: Time to Put Patient Safety First. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2701-2705, 2023.

Treatment of Vaginal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (VaIN)

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN), the presence of noninvasive squamous cell atypia, is classified by the degree of involvement of the epithelium, as follows:

- VaIN 1 is defined as involvement of the upper one-third of the epithelial thickness.

- VaIN 2 is defined as involvement of the upper two-thirds of the epithelial thickness.

- VaIN 3 is defined as involvement of more than two-thirds of the epithelial thickness. VaIN 3 lesions that involve the full thickness of the epithelium are called carcinoma in situ.

VaIN is associated with a high rate of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and is thought to have an etiology that is similar to that of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).[1,2,3]

The cervix and vulva are carefully evaluated because vaginal carcinoma in situ is associated with other genital neoplasia, and in some cases, may be an extension of CIN. Vaginal carcinoma in situ is often multifocal and commonly occurs in the vaginal vault. For more information, see Cervical Cancer Treatment.

The extent and type of surgical treatment needed is dependent upon anatomical location, evidence of multifocality, general patient comorbidities, and other specific factors (e.g., anatomical distortion of vaginal vault from prior hysterectomy).[4]

Treatment Options for VaIN

The following treatments have not been directly compared in randomized trials, so their relative efficacy is uncertain.[Level of evidence C3]

Treatment options for VaIN include the following:

- Laser therapy [5] after biopsy to rule out invasive components that could be missed with this treatment approach.

- Wide local excision with or without skin grafting.[6]

- Partial or total vaginectomy, with skin grafting for multifocal or extensive disease.[7]

- Intravaginal chemotherapy with 5% fluorouracil (5-FU) cream. This option may be useful in the setting of multifocal lesions.[5,8]

- Intracavitary radiation therapy.[9,10] Because of its attendant toxicity and inherent carcinogenicity, this treatment is primarily used in the setting of multifocal or recurrent disease, or when the risk of surgery is high.[1] The entire vaginal mucosa is usually treated.[11]

- Imiquimod cream 5%, an immune stimulant used to treat genital warts, is an additional topical therapy that has a reported complete clinical response rate of 50% to 86% in small case series of patients with multifocal high-grade HPV-associated VaIN 2 and VaIN 3.[12] However, it is investigational, and it may have only short-lived efficacy.[13]

Women with VaIN 1 can usually be observed carefully without ablative or surgical treatment because the lesions often regress spontaneously. VaIN 2, the intermediate grade, is managed by careful observation or initial treatment. Although the natural history of VaIN is not precisely known because of its rarity, patients with VaIN 3 are presumed to be at substantial risk of progression to invasive cancer and are treated immediately. Lesions with hyperkeratosis respond better to excision or laser vaporization than to 5-FU.[4]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

-

Eifel PJ, Klopp AH, Berek JS, et al.: Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al., eds.: DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2019, pp 1171-1210.

-

Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Schwartz SM, et al.: A population-based study of squamous cell vaginal cancer: HPV and cofactors. Gynecol Oncol 84 (2): 263-70, 2002.

-

Smith JS, Backes DM, Hoots BE, et al.: Human papillomavirus type-distribution in vulvar and vaginal cancers and their associated precursors. Obstet Gynecol 113 (4): 917-24, 2009.

-

Wright VC, Chapman W: Intraepithelial neoplasia of the lower female genital tract: etiology, investigation, and management. Semin Surg Oncol 8 (4): 180-90, 1992 Jul-Aug.

-

Krebs HB: Treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia with laser and topical 5-fluorouracil. Obstet Gynecol 73 (4): 657-60, 1989.

-

Cheng D, Ng TY, Ngan HY, et al.: Wide local excision (WLE) for vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN). Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 78 (7): 648-52, 1999.

-

Indermaur MD, Martino MA, Fiorica JV, et al.: Upper vaginectomy for the treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193 (2): 577-80; discussion 580-1, 2005.

-

Stefanon B, Pallucca A, Merola M, et al.: Treatment with 5-fluorouracil of 35 patients with clinical or subclinical HPV infection of the vagina. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 17 (6): 534, 1996.

-

Chyle V, Zagars GK, Wheeler JA, et al.: Definitive radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vagina: outcome and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 35 (5): 891-905, 1996.

-

Graham K, Wright K, Cadwallader B, et al.: 20-year retrospective review of medium dose rate intracavitary brachytherapy in VAIN3. Gynecol Oncol 106 (1): 105-11, 2007.

-

Kang J, Wethington SL, Viswanathan A: Vaginal cancer. In: Halperin EC, Wazer DE, Perez CE, et al., eds.: Perez & Brady's Principles and Practice of Radiation Oncology. 7th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2018, pp 1786-1816.

-

Iavazzo C, Pitsouni E, Athanasiou S, et al.: Imiquimod for treatment of vulvar and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 101 (1): 3-10, 2008.

-

Haidopoulos D, Diakomanolis E, Rodolakis A, et al.: Can local application of imiquimod cream be an alternative mode of therapy for patients with high-grade intraepithelial lesions of the vagina? Int J Gynecol Cancer 15 (5): 898-902, 2005 Sep-Oct.

Treatment of Stage I Vaginal Cancer

The treatment options for stage I vaginal cancer have not been directly compared in randomized trials.[Level of evidence C2] Because of differences in patient selection, expertise in treating local disease, and staging criteria, it is difficult to determine whether there are differences in disease control rates.

Treatment Options for Stage I Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) of the Vagina

Treatment options for stage I SCC of the vagina superficial lesions less than 0.5 cm thick include the following:

- Radiation therapy.[1,2,3,4]

- These tumors may be amenable to intracavitary brachytherapy alone,[1] but treatment usually begins with external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT).[2]

- EBRT is required for bulky lesions or lesions that encompass the entire vagina.[1] For lesions in the lower third of the vagina, elective radiation therapy is often administered to the patient's pelvic and/or inguinal lymph nodes.[1,2]

- Surgery.[5]

- Wide local excision or total vaginectomy with vaginal reconstruction may be performed, especially in lesions of the upper vagina. In cases with close or positive surgical margins, adjuvant radiation therapy is often added.[6]

Treatment options for stage I SCC of the vagina lesions more than 0.5 cm thick include the following:

- Surgery.[5]

- For lesions in the upper third of the vagina, radical vaginectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy should be considered. Construction of a neovagina may be performed if feasible and if desired by the patient.[6,7]

- In lesions of the lower third, inguinal lymphadenectomy should be considered. In cases with close or positive surgical margins, adjuvant radiation therapy should be considered.[6]

- Radiation therapy.[1,2,3,4]

- EBRT [2] and/or combination of interstitial and intracavitary radiation therapy may be administered to a dose of at least 75 Gy to the primary tumor.[1,8]

- For lesions of the lower third of the vagina, elective radiation therapy of 45 Gy to 50 Gy is given to the pelvic and/or inguinal lymph nodes.[1,2]

Treatment Options for Stage I Adenocarcinoma of the Vagina

Treatment options for stage I adenocarcinoma of the vagina include the following:

- Surgery.

- Total radical vaginectomy and hysterectomy with lymph node dissection are indicated because the tumor spreads subepithelially.

- The deep pelvic lymph nodes are dissected if the lesion invades the upper vagina, and the inguinal lymph nodes are removed if the lesion originates in the lower vagina.

- Construction of a neovagina may be performed if feasible and if desired by the patient.[6]

- In cases with close or positive surgical margins, adjuvant radiation therapy is often given.[6,7]

- Radiation therapy.

- Intracavitary and interstitial radiation are administered to a dose of at least 75 Gy to the primary tumor.[1]

- For lesions in the lower third of the vagina, elective radiation therapy of 45 Gy to 50 Gy is given to the pelvic and/or inguinal lymph nodes.[1,9]

- Combined local therapy in selected cases, which may include wide local excision, lymph node sampling, and interstitial therapy.[10]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

-

Perez CA, Camel HM, Galakatos AE, et al.: Definitive irradiation in carcinoma of the vagina: long-term evaluation of results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 15 (6): 1283-90, 1988.

-

Frank SJ, Jhingran A, Levenback C, et al.: Definitive radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 62 (1): 138-47, 2005.

-

Tran PT, Su Z, Lee P, et al.: Prognostic factors for outcomes and complications for primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina treated with radiation. Gynecol Oncol 105 (3): 641-9, 2007.

-

Lian J, Dundas G, Carlone M, et al.: Twenty-year review of radiotherapy for vaginal cancer: an institutional experience. Gynecol Oncol 111 (2): 298-306, 2008.

-

Tjalma WA, Monaghan JM, de Barros Lopes A, et al.: The role of surgery in invasive squamous carcinoma of the vagina. Gynecol Oncol 81 (3): 360-5, 2001.

-

Stock RG, Chen AS, Seski J: A 30-year experience in the management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: analysis of prognostic factors and treatment modalities. Gynecol Oncol 56 (1): 45-52, 1995.

-

Rubin SC, Young J, Mikuta JJ: Squamous carcinoma of the vagina: treatment, complications, and long-term follow-up. Gynecol Oncol 20 (3): 346-53, 1985.

-

Andersen ES: Primary carcinoma of the vagina: a study of 29 cases. Gynecol Oncol 33 (3): 317-20, 1989.

-

Chyle V, Zagars GK, Wheeler JA, et al.: Definitive radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vagina: outcome and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 35 (5): 891-905, 1996.

-

Senekjian EK, Frey KW, Anderson D, et al.: Local therapy in stage I clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina. Cancer 60 (6): 1319-24, 1987.

Treatment of Stages II, III, and IVa Vaginal Cancer

The treatment options for stages II, III, and IVa vaginal cancer have not been directly compared in randomized trials.[Level of evidence C2] As a result of differences in patient selection, expertise in treating local disease, and staging criteria, it is difficult to determine whether there are differences in disease control rates.

Radiation therapy is the most common treatment for patients with stages II, III, and IVa vaginal cancer.

Treatment Options for Stages II, III, and IVa Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) and Adenocarcinoma of the Vagina

Treatment options for stage II SCC and adenocarcinoma of the vagina, stage III SCC and adenocarcinoma of the vagina, and stage IVa SCC and adenocarcinoma of the vagina include the following:

- Radiation therapy.

- External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) alone or in combination with interstitial and/or intracavitary brachytherapy.[1,2,3,4,5] For example, EBRT for a period of 5 to 6 weeks (including the pelvic lymph nodes) followed by an interstitial and/or intracavitary implant for a total tumor dose of 75 Gy to 80 Gy and a dose to the lateral pelvic wall of 55 Gy to 60 Gy.[1,2,3]

- For lesions in the lower third of the vagina, elective radiation therapy of 45 Gy to 50 Gy is given to the pelvic and/or inguinal lymph nodes.[1,2,6]

- Surgery.

- Radical vaginectomy or pelvic exenteration is performed with or without radiation therapy.[7,8,9,10]

- Chemoradiation.[11]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

-

Perez CA, Camel HM, Galakatos AE, et al.: Definitive irradiation in carcinoma of the vagina: long-term evaluation of results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 15 (6): 1283-90, 1988.

-

Chyle V, Zagars GK, Wheeler JA, et al.: Definitive radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vagina: outcome and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 35 (5): 891-905, 1996.

-

Frank SJ, Jhingran A, Levenback C, et al.: Definitive radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 62 (1): 138-47, 2005.

-

Tran PT, Su Z, Lee P, et al.: Prognostic factors for outcomes and complications for primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina treated with radiation. Gynecol Oncol 105 (3): 641-9, 2007.

-

Lian J, Dundas G, Carlone M, et al.: Twenty-year review of radiotherapy for vaginal cancer: an institutional experience. Gynecol Oncol 111 (2): 298-306, 2008.

-

Andersen ES: Primary carcinoma of the vagina: a study of 29 cases. Gynecol Oncol 33 (3): 317-20, 1989.

-

Rubin SC, Young J, Mikuta JJ: Squamous carcinoma of the vagina: treatment, complications, and long-term follow-up. Gynecol Oncol 20 (3): 346-53, 1985.

-

Stock RG, Chen AS, Seski J: A 30-year experience in the management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: analysis of prognostic factors and treatment modalities. Gynecol Oncol 56 (1): 45-52, 1995.

-

Tjalma WA, Monaghan JM, de Barros Lopes A, et al.: The role of surgery in invasive squamous carcinoma of the vagina. Gynecol Oncol 81 (3): 360-5, 2001.

-

Boronow RC, Hickman BT, Reagan MT, et al.: Combined therapy as an alternative to exenteration for locally advanced vulvovaginal cancer. II. Results, complications, and dosimetric and surgical considerations. Am J Clin Oncol 10 (2): 171-81, 1987.

-

Rajagopalan MS, Xu KM, Lin JF, et al.: Adoption and impact of concurrent chemoradiation therapy for vaginal cancer: a National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) study. Gynecol Oncol 135 (3): 495-502, 2014.

Treatment of Stage IVb Vaginal Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage IVb Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) and Adenocarcinoma of the Vagina

Treatment options for stage IVb SCC and adenocarcinoma of the vagina include the following:

- Radiation therapy (for palliation of symptoms) with or without chemotherapy.

For patients with stage IVb disease, current therapy is inadequate. No established anticancer drugs have demonstrated proven clinical benefit, although patients are often treated with regimens used to treat cervical cancer.

Concurrent chemotherapy using fluorouracil or cisplatin-based therapy and radiation therapy is sometimes advocated on the basis of results extrapolated from cervical cancer management strategies.[1,2,3] Evidence is limited to small case series, and the incremental impact on patient survival and local disease control is not well defined.[Level of evidence C3] For more information, see Cervical Cancer Treatment.

Because stage IVb vaginal cancer is rare, these patients should be considered candidates for clinical trials to improve survival or local control. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

-

Grigsby PW: Vaginal cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 3 (2): 125-30, 2002.

-

Dalrymple JL, Russell AH, Lee SW, et al.: Chemoradiation for primary invasive squamous carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Gynecol Cancer 14 (1): 110-7, 2004 Jan-Feb.

-

Samant R, Lau B, E C, et al.: Primary vaginal cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiation using Cis-platinum. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 69 (3): 746-50, 2007.

Treatment of Recurrent Vaginal Cancer

Patients with recurrent vaginal cancer have a very poor prognosis. Most recurrences occur in the first 2 years after treatment.

In centrally recurrent vaginal cancers, some patients may be candidates for pelvic exenteration or radiation therapy. In a large series, only 5 of 50 patients with recurrence were salvaged using surgery or radiation therapy. All five of these salvaged patients originally presented with stage I or II disease and had tumor recurrence in the central pelvis.[1]

No established anticancer drugs have demonstrated proven clinical benefit, although patients are often treated with regimens used to treat cervical cancer. If patients are eligible, participation in clinical trials should be considered. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

-

Stock RG, Chen AS, Seski J: A 30-year experience in the management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: analysis of prognostic factors and treatment modalities. Gynecol Oncol 56 (1): 45-52, 1995.

Latest Updates to This Summary (02 / 16 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

General Information About Vaginal Cancer

Updated statistics with estimated new cases and deaths for 2024 (cited American Cancer Society as reference 3).

Treatment Option Overview for Vaginal Cancer

Added Fluorouracil Dosing as a new subsection.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of vaginal cancer. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewer for Vaginal Cancer Treatment is:

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Vaginal Cancer Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/vaginal/hp/vaginal-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389242]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's Email Us.

Last Revised: 2024-02-16